AI-Driven Investing: Building a Robo-Advisor That People Actually Trust

The idea of letting software manage money used to feel reckless. Today, it’s becoming the default. As fintech keeps expanding into territory once reserved for human advisors, the real question is no longer “Will users trust automation?” but “Can we design automation that deserves their trust?” Modern investment platforms, especially those serving fast-moving fintech ecosystems like digital finance services, now depend on systems that are both intelligent and predictable.

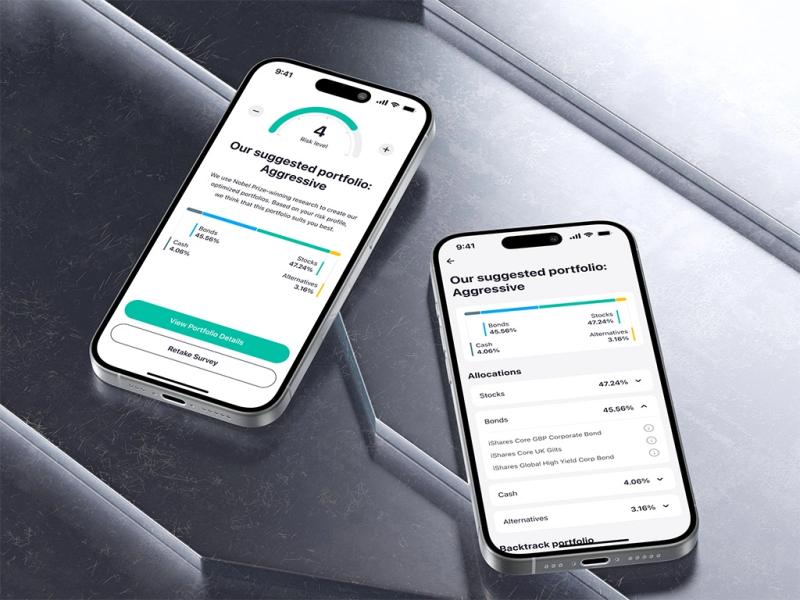

A robo-advisor sits at the intersection of these two demands. Under the hood, it’s a mix of math, market data, and machine learning. But for the user, it should feel like a quiet, competent assistant that understands their risk appetite better than they do — and never needs a coffee break.

Why robo-advisors exist in the first place

Traditional investment guidance has a bandwidth problem. Human advisors can only work with so many clients; automated systems can scale infinitely. That’s the economic explanation. But the emotional explanation is simpler: people feel overwhelmed. They open an investment app and see charts, acronyms, red arrows, green arrows, and somehow they are still expected to put together a coherent plan.

A good robo-advisor reduces friction by giving users a handful of decisions instead of hundreds. It translates abstract preferences — “I’m cautious but not terrified” — into actual portfolio allocations. And once it starts operating, it does what software does best: apply rules consistently.

What actually powers the system

The technical foundation is surprisingly similar across products. You take a clean interface, layer in a secure backend, and connect it to actual financial rails. The differentiation comes from how these pieces interact.

-

The UI must stay legible even when the data behind it isn’t. Investment apps that overwhelm users tend to lose them quickly.

-

The backend processes transactions, performs risk calculations, adjusts portfolios, and handles identity verification. It also needs enough redundancy so a market spike doesn’t bring the system down when users need it most.

-

The models — typically machine-learning based — forecast risk, cluster behavioral patterns, or optimize portfolio weights under constraints. These don’t replace theory; they operationalize it.

-

The integrations (brokerage APIs, custodial accounts, market-data feeds) provide the real-world execution layer.

Each part sounds straightforward until you try to build it. A robo-advisor isn’t a single feature — it’s the alignment of dozens of small decisions.

The development approach that actually works

Fintech projects tend to break when teams rush straight into implementation. Instead, the most reliable approach is iterative: start with a thin slice of functionality, test assumptions early, and gradually scale complexity. Teams building automated investing tools usually follow a pattern:

-

Understand the users — their financial literacy, tolerance for volatility, and preferred level of automation.

-

Define the real constraints — regulatory obligations, compliance boundaries, reporting requirements, and operational risks.

-

Design the behavior before the interface — meaning, define how the robo-advisor thinks before designing how it looks.

-

Prototype quickly, then validate with small user groups.

-

Harden the system with proper security, reliable data storage, and predictable calculations.

-

Integrate market data and custodians only when the core logic is stable.

-

Launch gradually — feature flags, soft rollouts, staged deployments.

This is where teams often discover how much fintech resembles building a distributed system: lots of moving parts, and each one matters. Even small errors — a timing mismatch, a rounding inconsistency, a poorly phrased onboarding question — can propagate into costly problems.

Costs: the unglamorous but unavoidable part

Budgets vary widely because the complexity varies widely. The biggest drivers are algorithm sophistication, custom UI work, backend architecture, and regulatory overhead. Simple versions can be built for a modest budget; fully featured systems that incorporate advanced modeling, dynamic rebalancing, and behavioral analytics move into six-figure territory. Many teams start with an MVP to reduce uncertainty and validate demand before committing to a full roadmap.

Should you build one at all?

For many companies, yes — but not because robo-advisors are trendy. They’re useful because they let small teams deliver capabilities that once required entire departments. They help younger users make sense of personal finance, and they help experienced investors automate boring but essential decisions. They also fit naturally into ecosystems where mobile experiences already dominate, which is why so many teams pair their investment tools with specialized mobile fintech development to maintain performance and clarity on smaller screens.

The long-term value comes from iteration. The first version doesn’t need to predict markets with uncanny accuracy. It just needs to give users a stable, understandable foundation. Over time, as models improve and data grows, the advisor can become smarter. Machine-learning-driven enhancements, especially those built with modern AI development practices, turn a basic portfolio engine into a personalized financial guide.

The bottom line

A robo-advisor is ultimately a design problem disguised as a financial one. You’re not just writing algorithms — you’re creating a system that people rely on during moments of uncertainty. If it behaves consistently, communicates clearly, and respects user intent, it becomes something users trust. And once trust is established, the technology finally has room to do what it’s meant to do: make investing simpler, calmer, and more human — even when it’s powered by machines.

Comments