Native iOS Development: Why It Still Matters

Most product teams make one big architectural decision very early: do we build native, or do we try to cover everything with one cross-platform codebase? On slides, that decision looks like a simple trade-off chart. In real life, it shows up later as sluggish scrolling, weird edge-case bugs, and release cycles that keep slipping.

Native iOS development is the boring, infrastructure-grade answer to that problem. It means building your app with the stack Apple actually designs for: Swift, Xcode, and the official SDKs. If you’ve ever browsed serious iOS development services, you’ll notice they all quietly assume this stack by default. There’s a reason: it behaves predictably and ages well.

What Native Actually Gives You

When you go native, there’s no translation layer between your code and the device. A tap is a tap, not a JavaScript event being piped through a bridge and back. That shows up in the details users rarely articulate but always feel: the way lists decelerate, the timing of animations, how fast the keyboard appears, how reliably push notifications arrive.

Native apps also stay closer to the platform’s evolution. When a new iOS version ships with features like updated widgets, new camera APIs, or Vision Pro capabilities, the native toolchain gets first-class support. Cross-platform frameworks catch up eventually—if the maintainers are still motivated and the plugin ecosystem doesn’t fracture along the way.

There’s a product angle here too. A native app that behaves like the rest of the system reduces cognitive load. Users don’t need to “learn” your app. It feels like part of the device, not a foreign object. It’s the same reason good websites feel effortless: they follow conventions instead of inventing their own physics.

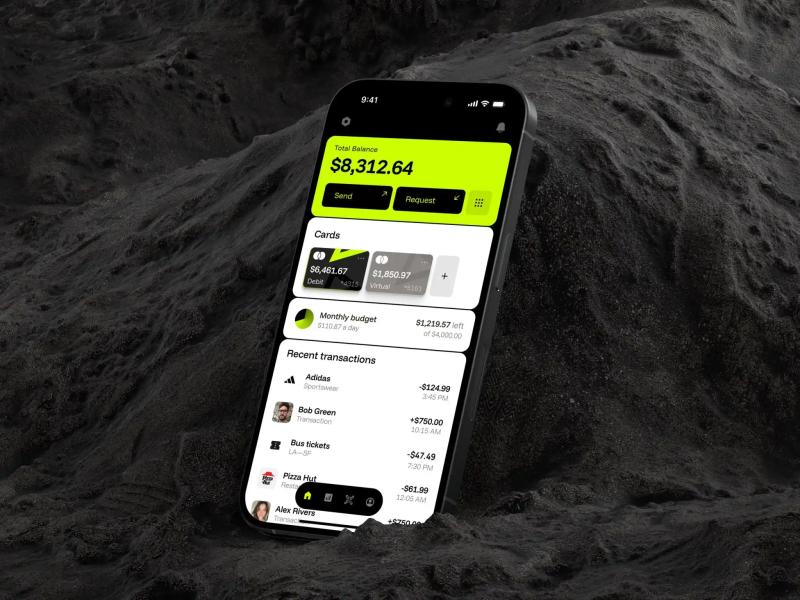

Behind that experience there’s usually disciplined work on structure and interface. Teams that care about this tend to invest in consistent product and interface design alongside the engineering effort, so the visual language and interaction model aren’t fighting the underlying platform.

When Native Is the Only Sensible Choice

There are a few situations where “maybe we can get away with cross-platform” quietly turns into “we should have gone native months ago”:

-

Performance-sensitive products. Real-time video, audio processing, AR, heavy animations, or anything that pushes the GPU will expose the overhead of hybrid layers quickly.

-

Deep integrations with iOS. Face ID, HealthKit, background tasks, advanced haptics, complex notifications, Vision Pro–specific flows—all of these are happiest in native code.

-

Long-term roadmaps. Early prototypes often look fine in a framework; the pain starts when you try to extend them. At some point, teams end up rewriting critical paths in native anyway.

-

Demanding audiences. Enterprise clients, design-driven consumer apps, or tools used all day by professionals will not tolerate laggy interactions or mismatched UI behavior for long.

If your app is essentially a simple content viewer or an internal tool with a short life span, cross-platform is defensible. Once you care about polish, latency, and longevity, native tends to win.

Inside the Native Toolkit

The native stack is intentionally cohesive. Xcode handles editing, debugging, simulators, and distribution. Swift gives you a modern, type-safe language that keeps improving every year. SwiftUI and UIKit cover different generations of UI building; many serious apps now use both, picking the right tool per screen or feature. Combine and async/await simplify the endless stream of “data changed, now update the UI” problems.

On top of that, you get CoreData or similar solutions for local storage, XCTest for unit and UI tests, and a CI/CD pipeline tied into TestFlight and App Store Connect. None of this is exotic; that’s the point. You’re not inventing a toolchain as you go—you’re using the one the platform itself is built on.

Picking the Right Team

Choosing who builds your app is almost as important as choosing how it’s built. Look for engineers who live in Xcode, not just “have used it.” Ask about their experience with SwiftUI migrations, push notification edge cases, App Store review issues, or handling large offline datasets. Then download a couple of apps they’ve shipped and actually use them.

Smooth navigation, consistent gestures, clean error handling, and sensible loading states are better proof than any proposal document. Teams that understand native iOS deeply tend to have an equally thoughtful approach to UI design workflows—creating layouts, states, and interactions that work with the platform instead of around it. That’s where well-run UI design practices pay off.

Cost, Trade-offs, and the Long View

Yes, native iOS development costs more upfront than a single shared codebase. You’re paying for platform-specific expertise and, if you also target Android, for separate work there too. But the real comparison isn’t just initial invoices; it’s the total cost of ownership over a few years.

Hybrid apps often start cheaper and become expensive as you chase performance problems, replace broken plugins, work around OS changes, and eventually rewrite critical pieces natively. Native apps, if architected well, tend to scale in a straight line: new features, refactors, and OS updates remain manageable.

In the end, the choice is strategic. If you’re validating a simple idea, cross-platform may be enough. If you’re building something you want people to rely on every day—and you’d like the codebase to still make sense three years from now—native iOS is still the most reliable foundation you can pick.

Comments