Dietary Fiber and the Microbiome: A New Perspective on Gut Health

For years, fiber was sold as plumbing. Eat more fiber so you stay regular. That message was not wrong, but it was incomplete. A new way to understand fiber for gut health is to treat fiber as an ecosystem tool, not just a digestion tool. You are not only feeding yourself. You are feeding a microbial community that helps convert food into signaling molecules that influence the gut lining, immune tone, and metabolic health.

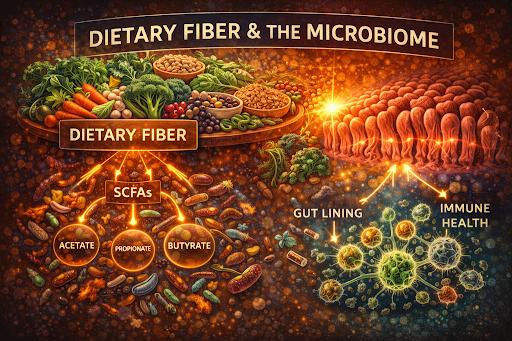

This is the perspective shift driving modern microbiome research. The microbiome is not just a list of bacteria. It is a chemistry factory. Dietary fiber is one of the main raw materials it uses. Harvard’s nutrition education materials describe how fiber can be fermented by gut microbes and how this fermentation produces short-chain fatty acids, key metabolites linked to gut health.

Once you see fiber through that lens, the daily question changes. It stops being, did I eat a salad today? Did I give my gut community the types of fibers it needs to do its best work?

Fiber is not one nutrient; it is a portfolio

A major misunderstanding in the public conversation is that fiber is one thing. It is not. Fiber is a category that includes compounds with very different behaviors in the gut.

Some fibers are fermentable and become fuel for microbes. That fermentation can increase short chain fatty acids like acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which are often discussed as links between diet, the microbiome, and immune function.

Some fibers are viscous, forming gel-like structures that can slow digestion and influence how the body handles glucose and cholesterol. Harvard’s fiber overview explains that fibers can be viscous and that some are fermentable while others are not.

Some fibers are less fermentable and primarily add bulk, which helps stool form and transit time.

This is why two people can both eat twenty-five grams of fiber and get different results. One may feel calmer and have a steadier appetite. The other may feel bloated and uncomfortable. The difference is often the mix of fiber types and how quickly they increase intake.

The microbiome angle that matters most is metabolites

Microbiome conversations often obsess over which bacteria are good or bad. The more actionable angle is what the microbes produce.

When microbes ferment fiber, they generate short-chain fatty acids. These compounds are widely discussed for their roles in gut barrier support and immune signaling. A 2024 review in the Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology describes short-chain fatty acids as a bridge between diet, gut microbiota, and host health.

This helps explain why fiber for gut health is not only about constipation. It is about the downstream chemistry that influences how resilient the gut lining is and how inflammatory signals are regulated over time.

A practical implication follows. If your diet is low in fermentable fibers, you may still be able to stay regular with certain foods, but you might be underfeeding the fermentation pathways that produce these beneficial metabolites.

Why modern diets struggle to deliver enough fiber

Most people do not miss fiber because they hate vegetables. They miss fiber because of the structure of modern meals.

Refined grains replace whole grains. Many snack foods are engineered to be low-residue. Fast meals are often protein plus sauce plus refined starch with minimal legumes and minimal intact plants. When that becomes normal, the microbiome gets less fermentable material and less variety.

Public health references consistently highlight that many adults fall short of recommended fiber intakes. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics notes an Adequate Intake benchmark of 14 grams per 1,000 calories, which is roughly 25 grams per day for women and 38 grams per day for men.

The goal is not to worship numbers. The goal is to recognize that most people have room to improve, and the microbiome often responds better to gradual increases than sudden jumps.

A new way to build fiber for gut health is to target three daily anchors

Instead of thinking, eat more fiber, think, and build three anchors that cover different fiber functions.

Anchor one is a viscous base

Examples include oats, barley, chia, flax, and psyllium-style fibers. Viscous fibers help create a steadier digestive pace and can be easier to tolerate for some people than large servings of raw vegetables.

Anchor two is a fermentable fuel source

Examples include beans, lentils, chickpeas, and certain prebiotic-rich foods. A 2025 review in Frontiers in Nutrition reports that adding fiber and polyphenol-rich foods can enrich short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria, supporting the idea that fermentable substrates matter for microbiome output.

Anchor three is an intact plant volume source

Examples include cooked vegetables, whole fruits, and mixed vegetables in soups and stews. These provide a blend of fibers and plant compounds, plus the simple benefit of volume and regularity support.

This three-anchor approach gives your gut community both structure and fuel, rather than relying on a single superfood.

A fresh example that shows why fiber type matters

Consider two lunches that have similar calories.

Lunch A is a chicken sandwich on white bread with chips.

Lunch B is a lentil bowl with cooked greens and a small serving of rice.

Lunch A may feel fine in the moment, but it tends to be lower in fermentable substrate. Lunch B feeds multiple fiber pathways at once. Lentils provide fermentable fibers. Cooked greens add a different fiber profile and plant compounds. Even the rice can become more gut-relevant if it is cooled and reheated, which can increase resistant starch, a fermentable carbohydrate type that many microbes use.

This is why fiber for gut health is best seen as a pattern, not a supplement you tack on at the end of the day.

Many readers first hear about practical gut routines through educators like Dr. Berg, but the strongest takeaway from the microbiome research is still simple: fiber variety and consistency matter more than any single hack.

What human trials are showing in real people

A common criticism of microbiome talk is that it is mostly theory. Human studies are increasingly testing practical changes.

A 2025 randomized controlled trial in Microorganisms evaluated four weeks of dietary fiber supplementation through higher fiber foods and reported changes in gut microbiota and bowel-related quality of life measures in healthy adults.

That kind of trial does not prove that one specific bacterium is the key to gut health. It supports a more grounded claim. When people raise fiber intake in a structured way, the microbiome composition and gut-related outcomes can shift, even over a short window.

The bigger message is that the gut is responsive. It does not require a year of perfect eating to see change. It requires consistent inputs.

Why going too fast backfires

If you increase fiber quickly, discomfort is common. Gas and bloating are not signs that you are doing it wrong. There are often signs that fermentation increases faster than your gut and microbiome are used to.

MedlinePlus notes that increasing dietary fiber too quickly can lead to gas, bloating, and cramps, and it advises adding fiber slowly.

The simplest rule is slow expansion.

Week one, add one fiber anchor per day.

Week two, add a second anchor on most days.

Week three, aim for a full daily pattern.

This avoids the classic mistake of adding a huge salad and a fiber supplement on the same day, then deciding fiber is not for you.

The overlooked role of variety

Many people improve fiber quantity without improving fiber diversity. They eat the same high fiber cereal daily and stop there.

Microbes respond to variety because different fibers feed different microbial groups and produce different metabolite patterns. The Harvard microbiome overview emphasizes that diet plays a major role in shaping microbiota, and it highlights the role of fiber in influencing the microbiome.

A practical diversity approach is rotation.

Rotate beans across lentils, chickpeas, and black beans.

Rotate grains across oats, barley, brown rice, and whole wheat.

Rotate produce colors across greens, orange vegetables, berries, and citrus.

You do not need complexity. You need repetition plus rotation.

Closing perspective

The newest and most useful perspective on fiber for gut health is that fiber is not a single number. It is a daily input that shapes microbial metabolism. When fiber is fermentable, microbes can convert it into short-chain fatty acids that connect diet to gut barrier function and immune signaling.

In practice, the best results tend to come from a fiber portfolio. Combine a viscous base, a fermentable fuel source, and intact plant volume. Increase slowly. Rotate sources. Treat fiber as a long-term ecosystem strategy rather than a short-term fix.

Post Your Ad Here

Comments